Recently, I have been at conferences in Las Vegas and Orlando.

Vegas, of course, is crazy with its extravagant fakery: Venice, Paris, Rome. It's amusing at first, then quite numbing. In Orlando, I could barely escape the conference center. When I emerged into the open air for a chat with colleagues, we sat in the sun on an empty lawn of Astroturf.

Baudrillard said of Disneyland that its fiction makes us believe the world outside is real. Disneyland's obvious artifice masks the fact that America is just as carefully constructed.

And what city could be more artificial than Venice, barely floating, loosely anchored to the caranto? And what could be more fake than a grass lawn: destructive, characterless, close-trimmed, pest-free, watered and fed?

And so, to today's topic.

What I am not saying and what I am trying to say

People sometimes mistake what I say about AI. They think I am saying:

AI is not really intelligent. It's not really reasoning. It's not really doing mathematics or being creative. AI is just simulating these things. Therefore, we must balance AI with the human element.

I am actually saying something different, closer to what Baudrillard says about Disneyland.

When we label machine learning as intelligence comparable to our own, we have to reduce, remove or devalue the key features of the human mind for that comparison to make sense. Turing removed nearly all traces of human communication from the Imitation Game in order for machines to be able to take part at all.

In this way, the artifice of machine intelligence keeps our attention from something else: the emptiness of so much of our thinking that we have reduced to such a shallowness that machines can imitate us.

I think it goes even further. When we claim a machine that passes the Turing test is passing for humans, or we claim that DeepSeek is reasoning, or that machines are close to superintelligence, we are re-imagining our own intelligence.

AI is becoming a mirror that reflects back to us not what we are but what we imagine ourselves to be.

When we celebrate AI for its processing speed, its pattern recognition, its unflagging consistency, we tacitly devalue the very aspects of human thinking that make it profound: our inconsistency, our physical messiness, the entanglement of our every thought with emotion, desire and disappointment, forgetting that our own thinking has never been purely cerebral.

When we marvel at AI's ability to mimic this without truly possessing it, we misrecognize what makes our own intelligence valuable, animating these technologies with our fantasies. We increasingly defer to the output of AI as authoritative precisely because it lacks the hesitation that comes with our understanding, our burden of the full weight and context of our thoughts and decisions.

So, here's what I am trying to say:

We're beginning to shape our ways of thinking, especially in business and technology, to more closely resemble the kinds of cognition that machines can easily replicate and measure: remaking human intelligence in the image of the machine. It does not need to be this way.

This pattern is not only found with artificial intelligence. In business, social media and entertainment, we're shifting toward cognitive processes that can be digitized, quantified, and made operational: celebrating these aspects while neglecting the ambiguous, contradictory elements of thought that have historically been the source of our most profound insights.

We're artificializing our own intelligence, making it more mechanical, more predictable, and more amenable to processes of measurement, optimization and control that are primarily economic rather than humane.

I am not saying we need more of the human element working alongside AI. I am saying that we’re eroding humanity in order for us to work alongside AI.

Quantifying our qualities

Human thinking is not limited to rationality; it emerges between conscious and unconscious processes, but also between personal and collective experience.

Our cognition is always charged with emotion, which isn’t an add-on to rational thought but woven into how we perceive, remember, and reason. From infancy onward, emotional resonance calibrates how we attend to people, places, and objects.

It's tempting to say that because machines (so far as we can tell) do not participate in that interplay, they are not doing real thinking.

That may be true, but its not particularly important to me. What does matter is that increasingly, we are rejecting the messiness of human life and thought in favour of ways of living and working that are closer to what machines can do.

This mechanization of human thought doesn't exist in isolation: it's part of a broader cultural shift toward quantification and transparency. In Byung-Chul Han's The Transparency Society, he argues that our contemporary culture is obsessed with turning everything into data, into something that can be counted, shared, and displayed.

Han writes about a relentless positivity: the elimination of friction, resistance, and Otherness in favor of efficiency, affirmation, and self-optimization. He contrasts this with negativity: the opacity, silence, critique and difference that is crucial for human thought.

Social media, and now AI systems, capitalize (literally) on positivity because they feed on our data: clicks, online behaviors, and textual inputs and feed them back to us in endless loops. In that sense, the focus on big data, optimization, and supposedly intelligent machines promotes a flattened, disembodied worldview. We become participants in our own alienation, handing over more aspects of our interior lives to systems that can quantify them without understanding them.

Our era encourages a kind of hyper-individualism, but merged at the same time with total connectivity. We share everything but remain profoundly alone in our curated social media bubbles. If we only seek what is transparent or “positive” in the sense of easy data, we lose access to the richer realm of human existence. We end up in a technological framework that only sees the world as something to be optimized.

In that scenario, the noise of digital connectivity drowns out introspection and even the unconscious. We have fewer opportunities to encounter ourselves if the timeline is always refreshing, if we are never silent.

Silence and dreams

Yet, as reflective people have discovered in every age, silence is essential for integrating our unconscious into conscious life. In the clamor of connectivity, we short-circuit that process.

To do this well, we need spaces of genuine emptiness: time away from the screen, time for contemplation, where we are not optimizing or performing. This emptiness is a break from the demands of Han's constant positivity, always making progress, always clicking or scrolling. It is in those silences that we can reflect on our real needs and the direction of our collective journey.

Historically, religion and spiritual practices often insisted on solitude, contemplation, even asceticism, to open up this domain of the unconscious. Even if one isn’t religious, there’s something crucial about the unscripted space where you’re not optimizing or performing.

As I said of AI before, social media mirrors back to us what we believe we must become, regardless of inner experiences that tell us otherwise. The interior space where one might dream or experience an unstructured flow of ideas gets squeezed out.

But the unconscious does not vanish; it remains, unacknowledged, influencing us in ways we do not see, the ways that Jung attended to: symbols, dreams, and the deeper psyche.

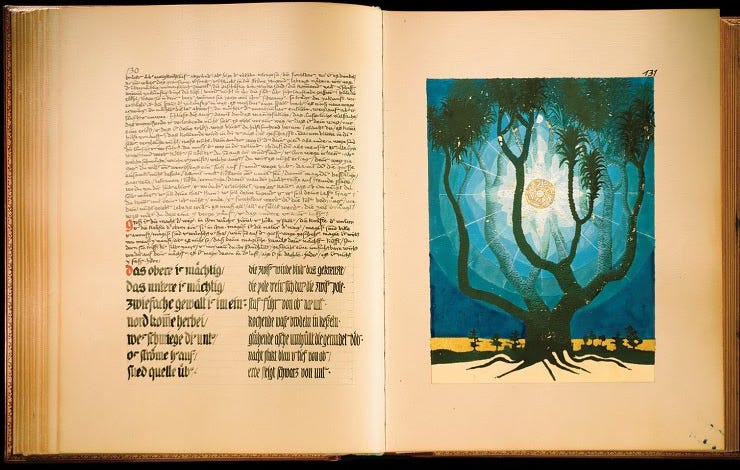

Our unconscious develops from the complexity of bodily experiences, emotions, and (to the Jungian) archetypal patterns that shape meaning over the course of a lifetime. That includes dreams and symbolic imagery that reorganize every event, entangling it with our individual past. This is how we form our self-identity, a narrative identity, often outside conscious awareness.

Nevertheless, I suspect a Jungian would say that we can’t help but project elements of our psyche onto the world around us, be that people, animals, or even technologies. So, to take the “child archetype,” we might see AI as a “newborn” set of systems, naive yet brimming with potential. Or we might consider the “wise old man” archetype: the super-intelligent oracle that might solve all problems.

The danger here isn't the specific archetype we work with (if Jungian archetypes are your thing) but that we anthropomorphize these systems, attributing to them wisdom, innocence, or malice that strictly belongs to the human domain; we forget to ask real questions about ourselves and our responsibilities.

But we, unlike the machine, cannot escape the unconscious, for at night, we dream our dreams: an endless reorganization of internal states, forging new and often bizarre connections that make us more resilient in the face of our fears, that enable us to integrate our experiences into a meaningful internal life. In our dreams, we can hold together contradictory meanings, symbolic ambiguities, and paradoxes. In dreams, we don’t resolve ambiguities; we cultivate them until they offer us insight if we would pay attention.

We may also attend to our dreams, our mythologies, our symbolic life. By bridging the conscious with the unconscious, we can see through the illusions we project onto AI. We have within us a vast interior world, one that’s messy, symbolic, and infinitely creative. If we take care not to reduce our existence to what can be digitized or formalized, we can live in that world more fully.

The business of thinking

In my next post, I'll pull on one of these threads a little more.

Our thinking about business - and therefore work - has been reduced to sterile enumeration more than any other aspect of life: everything is measured, scored, and optimized. We are told this is efficient, realistic and necessary and that any other view is naïve and unworldly.

That is an artifice.

what a great, thought-provoking read.

Another great and thought provoking post, Donald! The cynic in me (conjuring your recent 'cynics-critics' post), feels that capitalistic entities are overwhelmingly on a path to a complete focus on results and predicability of everything and minimizing (or avoiding completely) the unique perspectives, processes, and creativities that come from the conscious + subconscious human mind. I sense a very small minority of companies actually embrace the symbiosis of humans and tech while keeping both in balance. Seems to be a dying breed of business though - especially among corporations.