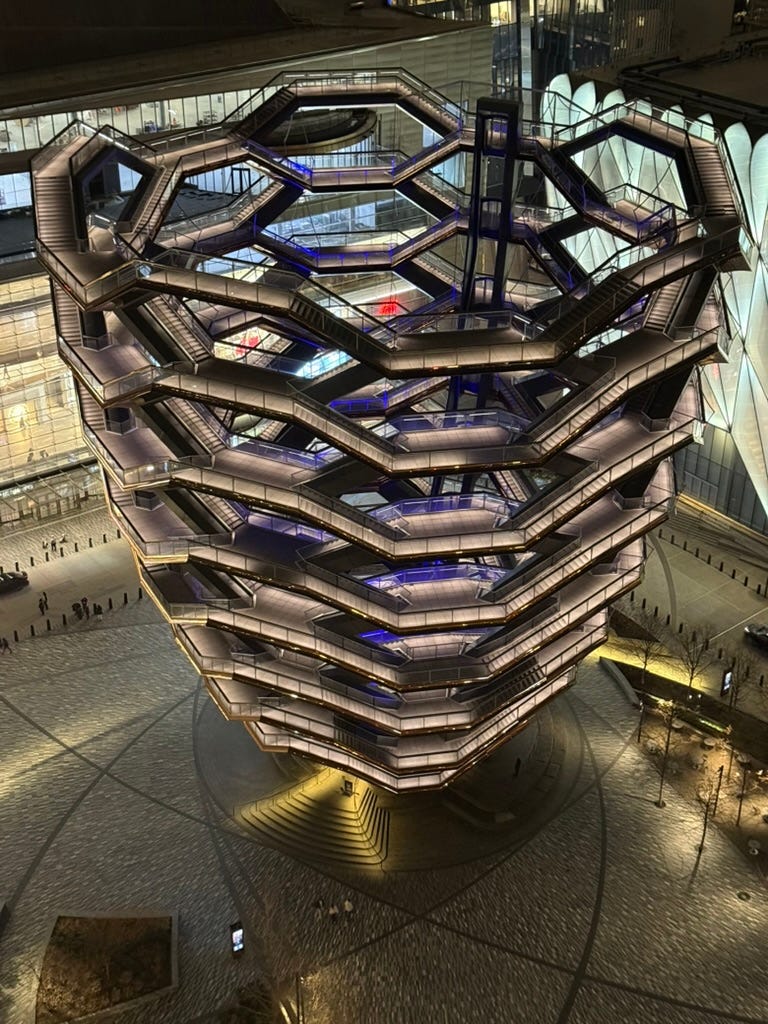

Vessel

Rethinking a New York landmark

Earlier this year, I stayed for several days in a friend's apartment in New York's Hudson Yards, overlooking Thomas Heatherwick's remarkable landmark, Vessel.

My view was unusual: looking down from above. I wonder if that literal different perspective made me consider the public space in ways that would not otherwise have come to mind. (I say public space rather than building, because that's how Heatherwick himself classifies it. It is designed to be entered and explored.

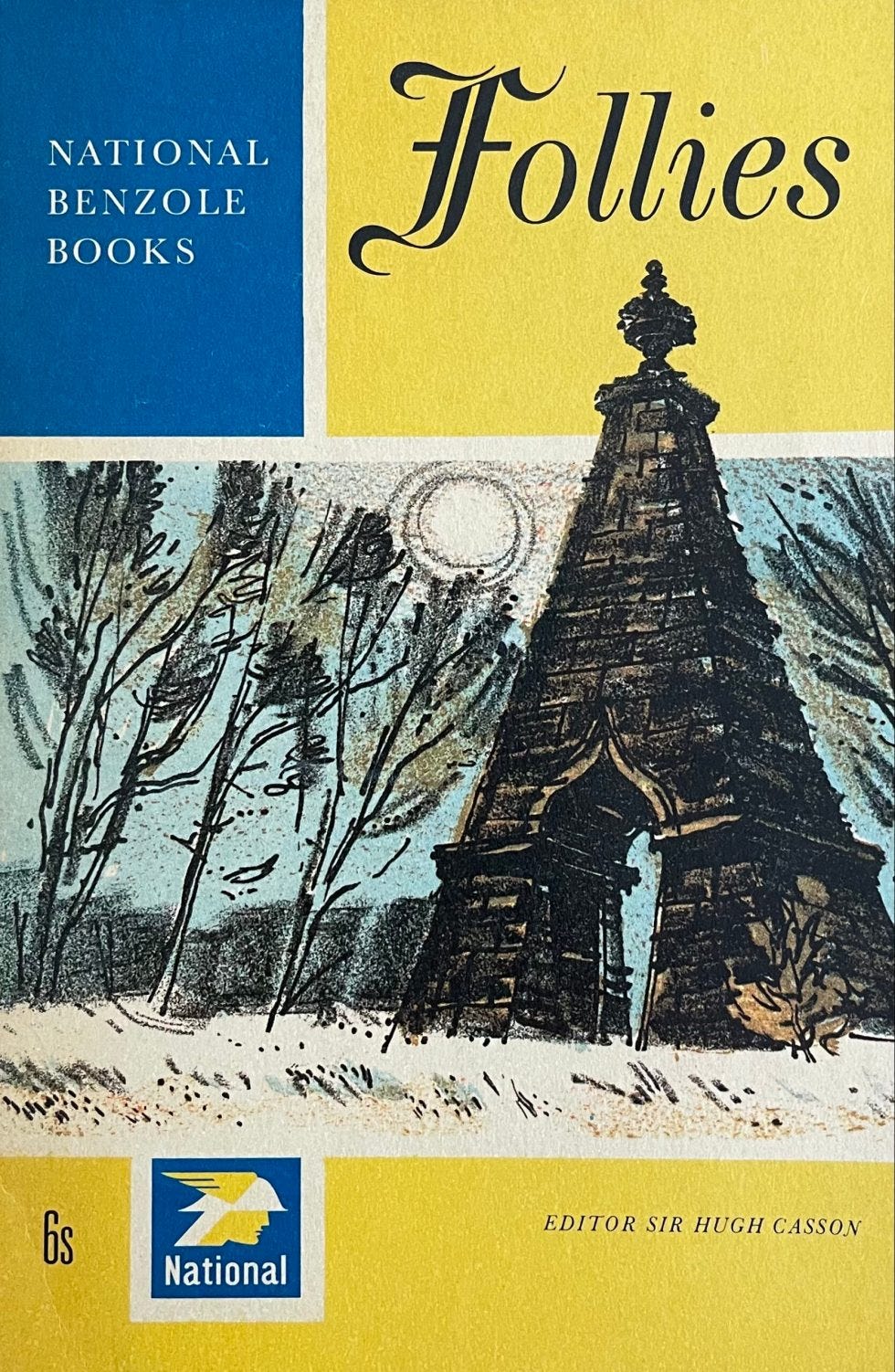

Now, about six months later, I have been thinking about Vessel again, because I have been reading Hugh Casson and E.M. Hatt's 1963 National Benzole guide to, mostly English, follies.

Is Vessel a folly?

As the introduction to that charming book notes, follyhood has to be felt as well as seen. Certainly, Vessel raised feelings: it can look quite lovely in certain lights, and in others, very plain. The scale struck me as odd; compared to the surrounding buildings, it's not very high: all you can really see is those luxury residential towers crowded around, the shopping center and a slice of river. There are no doubt better views from the nearby Edge skydeck, though I wouldn't dare go up there.

But Casson writes that, The mark of the true folly is that it was erected simply to satisfy and give pleasure to its builder. That doesn't feel true of Vessel, which is plainly commercial. But Casson also quotes Sansovino on Venice that it affects greatly to surprise the stranger, and that is certainly the case.

What strikes me about Vessel is how it seems designed primarily for self-documentation rather than contemplation. The historical follies described by Casson and Hatt were built to satisfy their creators, but Vessel exists to be consumed and reproduced digitally. With its inward-facing structure, it turns the gaze back on itself and the crowd. Its importance is that it is treated as important; it is photographed because it is photogenic. Visitors create a circulation of images that reference only more images. When they climb Vessel, are they really seeing New York, or merely seeing themselves seeing New York?

So, is Vessel a folly? Casson says that not every foolishly-conceived building is a folly. Equally, I think it's fair to say that not every folly is foolishly conceived, and I am not at all sure Vessel is foolish.

Traditional follies were often expressions of personal vision, however eccentric. Can Vessel, as a corporate commission, possess that same authentic eccentricity? Perhaps it represents an attempt to manufacture eccentricity at a corporate scale. The historical follies served very small audiences: the wealthy landowner and occasional visitors. Vessel serves millions.

And Vessel doesn't even pretend to be anything other than a spectacle for consumption. Traditional follies stood apart, often at the edges of an estate, removed from the house and functional buildings. There was a distance, both literal and figurative, between conventional living and folly creation. The historical follies embodied a kind of private vision made public. Vessel is a public vision designed to generate shared experiences, mediated through technology. And it doesn't stand apart from commerce; it facilitates it, being at the heart of a luxury shopping development.

Moreover, the historical follies, however eccentric, often attempted to direct attention toward something beyond the self: a loved one, a historical event, or an idea. Even the most self-aggrandizing tower built by a nobleman at least attempted to connect to some larger narrative about family, legacy, or power. Vessel connects to nothing but the experience of itself. Surrounded by selfie-takers, often well-equipped and artfully posing, it seems to embody a particular contemporary ennui.

Not so empty

But then, on my solitary walks at dawn, when almost no one is around, another thought stirs, not so bleak. The Vessel is lovely in the early morning light of Spring, so early that no visitors see it.

Beauty can be a reminder of what exists beyond our personal concerns. Could I see Vessel as at least attempting to create a new kind of beauty in an urban landscape otherwise dominated by utilitarian structures? Do people climbing Vessel experience something genuinely novel, creating meaning from that? Who am I to say this is empty?

Vessel, whatever its faults, at least provides a new kind of space for people to inhabit and interpret. Their selfies, posed and posted, are, after all, a form of storytelling, creating coherence between personal meaning and social belonging.

I wonder how Vessel will age? Unlike follies, which often deliberately engaged with mortality through their artificial ruins, Vessel, with its gleaming bronze structure, certainly doesn't aspire to ruin. The historical follies have acquired a patina of meaning through decades or centuries of existence. Will Vessel's bronze be allowed to age?

However, it holds up, in our accelerated culture, structures don't have the luxury of developing meaning slowly. The intention may have been the monetization of the sublime, but mortality has intruded in the most disturbing way possible. Vessel has been associated with real tragedy through multiple suicides, forcing its closure for years and significant modifications. Climbing the structure today, you are very aware of the mesh across the higher levels and that the uppermost is still closed.

Suicide is an extreme form of how cultural objects like Vessel can be used in ways that subvert their intended functions. Even the selfie-takers may be using the architecture ironically or critically rather than simply celebrating it. Vessel's corporate origins cannot completely determine its effects. Its purpose cannot be reduced to the creators' intentions. If the primary message was supposed to be look at me, everyone posing in the most mannered fashion in front of it is saying, No, look at me instead.

Vessel, in the long view happily, reminds me of how cultures continuously generate objects that exceed their original purposes. It will continue generating experiences and interpretations that surprise and challenge us, regardless of our critique.

So, I suspect Vessel does stand in the tradition of the folly, in a good way. Hugh Casson wrote that, There is no doubting that follies have been richly enjoyed, well worth the building. Regardless of whether I appreciate its aesthetics or its context, Vessel has raised for me the thoughts that good art can: about meaning, experience, authenticity, and the society that produced it.

As always, a thoughtful intersection of ideas I did not realize were related until you made the connection. Thank you. :{>